Now, We Think:Re/membering Es/sex

Clipped from the site of my homey,poet Marvin K. White

http://www.marvinkwhite.com

---

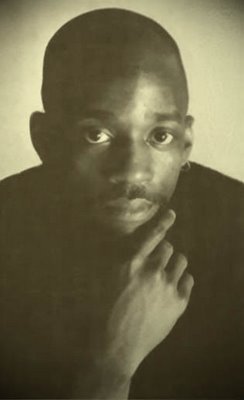

Essex Hemphill

April 16, 1957-November 4, 1995

Today, as I looked for tribute, for honor, I came across a friend whose work continues to speak and speaks in new ways, like me, the spirit of Essex.

FUNNY THING, ESSEX an open letter by Steven G. Fullwood

Funny thing, Essex, it really doesn't seem as if you're gone.

Don't get me wrong, now. I feel and mourn your death nearly every day, and often mention the significance of your work to other folk, and its impact on my life. In that respect, you're quite alive to me.

Recently, I had the extreme good fortune to witness Tracy Chapman in concert. And you know she worked us, let me tell you. Dreads falling all over the place, sister told stories about the many struggles you and I talked about, letting us all know truth never dies; similarly what can be described as African cultures never die, never cease to be. They have simply changed form exhibited most richly in African American cultural products like rap music, Vondou (some say "voodoo") and the way we folk talk with one another. Our language alone speaks of rivers, of resistance. Tracy's love for self and for people reminded me of your love, of your poems where black and gay men, faced with the prospect of death, managed to love and live fiercely. Truth under the dark of night, you believed, was still truth. Your love never stopped, even as your heart did. Tracy came in, jammed, and was out. Just like you.

Sometimes when I go to the library, books literally jump off the shelves and into my hands. Used to scare the devil out of me, but now I understand why these books came to me at certain times in my life. I was ready for the information, ready to see something different. Now, you can either accept this new idea or viewpoint, or reject it, but fact is, it's there. Similarly, I found your work through a friend. She gave me copies of your poems from In the Life: A Black Gay Male Anthology. I was so hungry for a different take on this homosexual thing, I almost died waiting for one. Although I knew there was something else, I couldn't articulate it or even fully imagine what it could be. I was just coming out. Your poetry helped guide me through this rite of passage, along with Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, and other men who, in one way or another, helped me to conceive something different about being black and homosexual. I read your work, and thought somebody loves me, somebody cares about me. I was overwhelmed by your simple words, your testimony. As a consequence, I worked to articulate and chronicle my own pains and joys about being African American, homosexual, and unapologetically funky. So I set out to find you, to personally thank you for your gift to me and others. Surely, you needed to know about me and my respect for you.

When I finally tracked you down, I decided simply talking to you wouldn't be enough. I had to see you. In the flesh. I knew you were sick, and your health was deteriorating, but you didn't let that stop you from doing your work. I invited you to my hometown, to host the late Marlon Riggs' extraordinary documentary, Black Is...Black Ain't. You strolled in, talked about Marlon -- his struggles and triumphs -- comfortably, almost serenely. Picked you up the next day to take you to a community reception in your honor, and I was quite salty when Black folk didn't show up. It was difficult, to say the least, to raise the funds and advertise your visit, in a town content with its conservative mores and values. It was even more difficult to know how the Black gay and lesbian folk in Toledo suffer because there are so few outlets in which to dialogue about the quality of their lives, without loud music and flashing disco lights. As a people normally defined by their genitalia's goings-on, I hoped to facilitate dialogues where we could question this idea, because, of course, it's ridiculous. When we passed out flyers, some people commented about the upcoming "party" I was hosting. Guess somebody figured it out, huh?

Your passing alarmed me, because your love and vitality were so immediate, so refreshing, when we met face-to-face. We laughed, testified, argued and agreed. While driving you to the airport, we talked about Black gay male bodies, and the importance to re-evaluate our lives as Black gay folk. I hugged you, and watched you toddle off to catch your plane back to Philadelphia. I never thought this is the last time I'll see you, alive, so thank you, thank you so very much, but thanking you doesn't seem like enough. You helped me save my life. How do I express my gratitude? How?

We're going to die, but how we "pass" into that state means everything. Energy doesn't die; it transforms. Our lives are much more than they appear. Bodies are laid to rest, but our souls continue to exist, on a different level. Ancestors work us in ways so simple, so esoteric, one can become aware of their connection to everything and nothing, just by listening and accepting all there is, in the moment. I hear you, Essex, and I know you hear me.

I may mourn your passing, but I celebrate you and your contributions, your resistance and love. I work to combat the fear and loathing that attempts to call our loving wrong. Anything that allows us to love is not, and can never be, wrong. We are witnessing what comes from the denial of this. And it's not love.

Recently, I heard someone say, "the body is vehicle, not the point," and that means so much to me. Your love is the point, Essex. That you cared to value and validate your experiences as a man, a lover of men, a person of African descent born in America -- these things work to inspire me and many others, until we, too, shall pass. When one of us passes, others will pick up our tools and forge ahead. This certainly doesn't sound like death to me.

Sounds like a whole lot of life.

"Funny Thing, Essex: An Open Letter" © 1996 by www.stevengfullwood.org

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home